Waterlow Centenary

Introduction

Historical background

Numbers printed

Characteristics of the stamps

Summary of the characteristics

Colours

Papers

Die types, Plates, Retouches

Printings, Paper

Perforation

A survey of the perforation

Bibliography

Waterlow Revisited I

by Jozef Wagemakers

(English translation by Willem Verhulst)

This year (1998) sees the centenary of the issue of the so-called 'Waterlow Stamps'. A good reason to pay attention, by way of a series of articles, to this fine and exciting issue. This first article provides an introduction, which summarizes the historical background, the numbers printed and various characteristics of the stamps.

The article was largely inspired by 'The Waterlow Issue of 1898' by Beales and Aglen, which is based on a study of the archives of Waterlow & Sons Ltd. (The sheets from these archives are known as the 'file-copies'.) With their publication, Beales and Aglen did pioneering work for the research into the Waterlow stamps. It is an indispensable work for those interested in the issue.

About a hundred years ago, the Chinese Imperial Post issued their second postage series. This series is known as the Waterlow Issue, after the printers Waterlow and Sons Ltd. According to current catalogues, the series was introduced on 28 January 1898.

Historical background

After the Tsungli Yamen (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) had agreed, on 20 March 1896, to set up an Imperial Postal Service (in the previous period there existed a Customs Mail), a number of changes had to take place. In the first place, it was decided to change over from a system based on the tael to a system based on dollars and cents and in the second place there had, naturally, a postage series to be issued. There was some haste in producing a postage series, as the Imperial Post was to be opened on 1 January 1897 (later postponed until after the Chinese New Year, 2 February 1897). The designer employed by the Inspectorate General of Customs, R.A. de Villard, submits a number of stamp designs in August 1896, also indicating that the stamps in stock, the 1885 small dragons and the 1894 Dowager series, can be used for overprinting in cents. The Inspector General of Customs, Sir Robert Hart, makes a selection from these designs. Hart strongly prefers to have the stamps produced in Britain, whereas Postal Secretary H. Kopsch prefers to have them printed in Japan. Initially, they are indeed printed in Japan, because it is cheaper there and they will be ready sooner. In a letter of 10 January 1897, Hart reports: 'We are getting postage stamp dies from Japan, being in a hurry; but I fancy we shall end by going to London.' (Hart to Campbell, his London agent)

Evidently, it was intended at the time that only the Dies were to be made in Japan, and that printing would take place in Shanghai. Ultimately, these stamps were printed in Japan, at the Tokyo Tsukiji Type Foundry. Because all this took much longer than expected, it was necessary to use De Villard's plan for overprinting. Initially, the remaining stocks of the small dragons and the Dowagers were overprinted; when this turned out to be insufficient to meet the demand for stamps, a new printing was made of the Dowager series, especially for overprinting. This turned out to be insufficient as well. Especially the introduction of parcel post and money orders created the need for high postage values. The Shanghai storeroom contained a number (650,000) of stamps intended for a stamp-duty that was never introduced, the so-called Red Revenues. These stamps were then also overprinted.

The Japan Printing (SG 96-107) was introduced on 16 August 1897. Somewhere between the letter of 10 January and 26 May 1897 it was nevertheless decided to have the subsequent order executed by Waterlow, on the basis of the original designs. The gentlemen at Waterlow's, however, had their own ideas about the designs and thought they could improve on them, to Sir Robert Hart's great dissatisfaction, as is made clear by the following quotation: 'Your postal telegrams have driven me wild this week! Having supplied approved designs, Waterlow had simply to execute them; so a fortnight has been lost, and I suppose a couple of hundred pounds over this 'lace' discussion. I hope there will be no delay and that your assurance that supply would commence to come forward two months after arrival of designs, will be made good. The central designs - dragon, fish and swan - mark the 3 values well, and the border flower has some significance in Chinese eyes. As far as counterfeiting is concerned, would lace be a bit more difficult for experts than those clever little things you call 'dots'? It's curious how English manufacturers dislike adhering to designs and always suggest some improvement as they think, but which generally is the wrong thing for the other end! Henderson, Bisbee and myself have all had these experiences! You ought simply to have said to Waterlow 'There are the designs, follow them faithfully in every respect'. (Hart to Campbell, 5 September 1897)

The only alteration that had been ordered is the changing of the inscription from 'Imperial Chinese Post' into 'Chinese Imperial Post'. There do exist Waterlow Die-proofs of the original designs, but these were never used for the eventual stamps.

Numbers printed

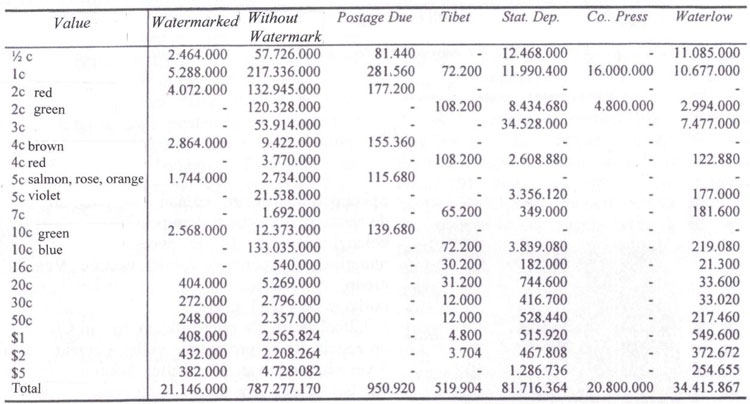

(Table 1: Numbers printed of the different values, with and without watermark)

Value |

Watermarked |

Without Watermark |

1/2c |

2.464.000 |

57.726.000 |

1c |

5.288.000 |

217.336.000 |

2c deep red |

4.072.000 |

132.945.000 |

2c deep green |

- |

120.328.000 |

3c |

- |

53.914.000 |

4c deep chestnut |

2.864.000 |

9.422.000 |

4c scarlet |

- |

3.770.000 |

5c salmon, rose, orange |

1.744.000 |

2.734.000 |

5c mauve |

- |

21.538.000 |

7c |

- |

1.692.000 |

10c deep green |

2.568.000 |

12.373.000 |

10c blue |

- |

133.035.000 |

16c |

- |

540.000 |

20c |

404.000 |

5.269.000 |

30c |

272.000 |

2.796.000 |

50c |

248.000 |

2.357.000 |

$1 |

408.000 |

2.565.824 |

$2 |

432.000 |

2.208.264 |

$5 |

382.000 |

4.728.082 |

Total |

21.146.000 |

787.277.170 |

Neither Waterlow nor the Chinese Post Office kept records of the exact numbers of stamps printed. M.D. Chow has published a list based on material supplied by Juan Mencarini (a Chinese Post Office employee). The following table shows the numbers as accurately as possible. The numbers of the watermark stamps are based on the file-copies.

In total, over 800 million stamps were printed. There are indications that Mencarini based himself on the archives up to April 1912. If this is so, the numbers cannot possibly include the Waterlow overprints (SG 218-32), in which case the real numbers will be a couple of hundreds of millions higher.

Characteristics of the stamps

The stamps can be subdivided on the basis of ten characteristics (in descending order of importance): Image, Value, Colour, Paper, Die, Plate, Retouches, Printing and Shades, Position of the paper, Perforation. The following gives a summary of these characteristics.

Image

The series consists of 3 images (designs). The values up to and including the 10c show a dragon - symbol of the Empire - at the centre. At the top there is the Wan nian qing ('10,000 years of green'), a Chinese plant symbolizing immortality. The 16, 20, 30 and 50c values have the carp as their central figure. The carp symbolizes fast transport across water. At the top of the box there is a plant, probably a peony. The Dutch Studycircle has taken this carp as its symbol. The dollar values have the flying goose at the centre, symbolizing fast overland (!) transport. From these images, Master Dies - engravings without indication of values - were made.

Value

From the Master Dies, Dies were produced which included the indication of the values. Robson Lowe (Lowe, 1985) gives a detailed description of these Dies. The original series consists of 12 values: 1/2c, 1c, 2c, 4c, 5c, 10c, 20c, 30c, 50c and 1, 2 and 5 dollars. As a result of changes in the postal rates, 3c (1909), 7c (1909) and 16 cents (1906) were added later. In the literature, the different Dies are usually indicated by numbers, which were allotted at the printer's. There is a problem with regard to the numbering of these value Dies. The Master Die of the dragon stamps (no 2503) has a higher number than the value Dies. A possible explanation is that Waterlow's started numbering on the basis of De Villard's original drawings. In an article in the China Clipper, Benny So (So, 1971) reports the rare and unique discovery of De Villard's original drawings. Apart from that, there is a similar set at the Beijing postal museum. What is unique about these drawings, however, is that they are accompanied by the Die proofs of the Japan printing, while above each drawing a Waterlow Die proof, with a number, has been mounted. If these are genuine Waterlow Die proofs, they may help us to solve the numbering puzzle. The illustrations in So include the Die numbers. The 20 and 30c and the 2 and 5 dollars are not represented. Judging from the illustrations, they appear to be direct stamp-size copies of the drawings. These Dies were rejected, since the text had to be changed from Imperial Chinese Post into Chinese Imperial Post. Apparently, Waterlow's operated the numbering system as follows: the 1/2c Die is number 2487, irrespective of the stage. Therefore, subsequent 1/2c Dies also receive number 2487. When we put the information from So and Lowe side by side, we arrive at the following:

(Table 2: Die numbers for the different values)

|

1/2 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

10 |

20 |

30 |

50 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

So |

2487 |

2488 |

2489 |

2490 |

2491 |

2492 |

|

|

2495 |

2496 |

|

|

Lowe |

2487 |

2488 |

2489A |

2490 |

2491 |

2492 |

2493 |

2494 |

2495A |

2496 |

2497 |

2498A |

Summary of the characteristics of the stamps

The Master Dies have the numbers 2503 (dragon), 2495 (carp) and 2498 (goose). Furthermore, we have a Master Die nr 2499 with white lettering on a coloured background. Of this, there also exists the value Die of the 2c (nr 2489). Neither of these was used for the eventual stamps. Die nr 2500 is an unused design of the Master Die for the carps. Two Die numbers are missing from the archives, viz. 2501 and 2502. These may have been designs for the dollar values or for their background plates. The 16c has Die nr 3956, and the 3 and 7 cents have 4412 and 4413 respectively.

Colours

These include the colours as intended by the printers; they are the following:

(Table 3: Colours of the different values)

1/2c brown |

16c olive-green |

1c ochre |

20c claret |

2c deep red and deep green(1908) |

30c rose |

3c grey-green |

50c green |

4c deep chestnutand scarlet(1909) |

$1 deep red and salmon |

5c salmon, rose, orange and mauve(1905) |

$2 claret and yellow |

7c crimson-lake |

$5 deep green and salmon |

10c deep green and blue(1908) |

|

In the 5c, the orange is the result of a mixing error of the ink, and not intentionally used as a new colour. The colour changes in the 2, 4, 5 and 10 cents were effected to comply with U.P.U. requirements (although China was not a member). There also exist colour proofs of all values, on white paper without watermark, imperforate and in colours not issued. The 1/2c is known in 9 colours, the 1c in 2 and the others in 1 colour.

Paper

The series is found on three types of paper, initially on watermarked paper and later on 2 types of paper without watermark.

Watermarked paper

The watermark used in this issue is the same as in the small dragons, the  Dowagers and the Japan printing, the so-called yin-yang or tai chi watermark.

Dowagers and the Japan printing, the so-called yin-yang or tai chi watermark.

When the printing order was granted to Waterlow's, a batch of watermarked paper was still on hand in Shanghai, this was shipped to Waterlow's with the instruction to use this paper and, when they ran out, to continue printing on plain paper. On this, Mencarini (Report..., 1906) reports the following:

'On the 26th May 1899 the stock of watermarked paper, 110 reams, enough to print about 13 million stamps, was forwarded to Messrs. Waterlow & Sons to print without regard to the stamps fitting the watermark, after the exhaustion of which paper the stamps were to be printed on plain paper.'

These few lines have put quite a few pens in motion, in the first place Mencarini mentions the date 26 May 1899. This is strange, because the first printing of the Waterlow Issue is dated 15 October 1897. If the date should read 26 May 1897, it lies well before the date on which the Japan printing was issued, or even printed. Why then was this paper not used for the Japan printing, rather than having it shipped all the way to Britain? Curious! The second point that raised quite a few questions is his remark '110 reams, enough to print about 13 million stamps'. From the file-copies it appears that at least 21 million stamps were printed on watermarked paper, so the obvious question is which paper Mencarini had in mind. There is a simple answer to it: a 'ream' is a unit of measure for paper, only it is not a fixed unit, as it may consist of 480, 500 or 516 sheets. De Villard reports in great detail on having used 17 reams and 42 sheets, 8542 sheets in total, for the Dowager issue (De Villard, 1991). This implies that a ream would contain 500 sheets. Because the same type of watermarked paper is concerned here (though not necessarily from the same manufacturer), I assume that a ream of the Waterlow paper also consists of 500 sheets. A second consideration is that the paper used for the Red Revenues also contained 500 sheets per pack. A plate of the Waterlow stamps consists of 240 stamps, yielding 13,200,000 stamps by using 110 reams. Probably, this is Mencarini's assumption. Because the number printed is much higher, they may have been double sheets, which yield a printer's sheet after halving. Aglen gives a measure of 30 3/4 by 17 3/4 inch for a complete sheet. This seems a bit narrow to me, since it would leave no white edge after printing, while it is clear that the sheets were trimmed afterwards.

The watermark is always described as 'difficult to see', but excellent results can be achieved by using a somewhat better type of watermark-finder, such as Safe, Lindner or Morley-Bright, although the watermark in the stamps of the later printings is indeed far less visible. This has also given rise to the assumption that two types of watermarked paper were used, one thin and transparent and one thicker, far less transparent paper. It is more probable that only one type of watermarked paper was used, but that it did not have a very constant quality. There is a problem, however, with the dollar values. These were printed crosswise on the paper, causing the watermark to show lying on its side. It is impossible to prevent parts from being left without a watermark while cutting the paper. It is quite possible for rows of stamps to appear repeatedly without watermark, while they are printed on watermarked paper. The only way to find out is by measuring the size of the image, this may provide a definite answer as to which paper was used. In an article in the Journal, Peter Holcombe considers these problems at length.

Paper without watermark

After the watermarked paper had been exhausted, plain paper was used for further printing. At least two types of paper were used. At first, a rather nontransparent paper, later a thicker, but more transparent paper. The differences are slight (0.08 and 0.1 mm thickness respectively), and it is not always possible to ascertain which paper was used. According to Aglen, the later type was used from about 1912 onwards.

When was the paper without watermark first used? According to the file-copies, the first printing on paper without watermark dates from 25 August 1899. In China, they were not used until the stamps printed on watermarked paper were exhausted. Aglen reports April 1900 as the earliest date. To me, this seems very early. I have seen the 1/2c September 1901, the 1c July 1901 and the 2c November 1900. With regard to the 1/2c it is striking that the B.R.A.-overprints of April 1901 were made on stamps that had watermarks. It is therefore improbable that the 1/2c stamps without watermark were already in circulation at that time.

Die types

The value Dies were subjected to changes through the years; these, however, were not recorded by Waterlow's. Until now, the following dies are known: 1/2c, 1c, 2c and 5c: 3 dies, while 2 dies are known of the 3c, 4c, 7c, 10c, 20c, 30c, 50c, $1, $2 and $5.

Plates

The Dies were used to produce printplates. With the help of the Die, transferred to a steel roller, prints are embossed in a copper plate. The arrangement on the sheets is 12 panes (4 by 3) of 20 stamps (4 by 5) each for the original cent values, 240 stamps in total. The dollar values were printed in small sheets of 48 (8 by 6). The supplementary values of 3, 7 and 16c were printed in sheets of 200, 8 panes (4 by 2) of 25 stamps (5 by 5) each. The panes are separated horizontally by small strips (8 mm) and vertically by broader strips (30 mm). Probably the plates had a surface treatment after embossing. Plate numbers exist, but, with the exception of the 3c, they are very rare, as nearly all the plate numbers were cut off when the sheets were trimmed. The following plate numbers are known: 1/2c: 1 and 4, 1c: 1 and 6, 3c: 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and plate 2 of one of the dollar values. Until now, no plate numbers have been reported of the other values.

Retouches

Different stages of the plates exist, probably they were cleaned before each printrun and retouched where necessary. Thus, there are at least 5 stages of plate 1 of the 1c. The best-known of the retouches is probably the retouched yi in the 1c value (Ma 126d). In the book 'Waterlow Issue of 1898', literally hundreds of retouches are mentioned.

Printings

As the last point in matters dealing with printing we come to the Printings, i.e. the individual print orders per value. In the file copies, about 120 of them are dated. This is only a small part of all the printings there have been, probably 5 or 6 times as many. The shade of the ink is also connected with the printing, this is something else than the colour mentioned in section 3. If colour is what is meant, then a shade is a deviation in the colour intended, brought about by the inability to mix the ink with precision. Exaggerating, you may state that each printing is characterized by its own shade. Especially the 5c stands out, with its more than 20 different shades. In some cases these differences in printing ink can be made visible under UV-light. To a great extent this holds good for the 5c with the Waterlow imprint, to a lesser extent for the 2c red and the 3c. It may be fitting to comment briefly on the colours. The naming of shades is hopeless; Mencarini, for example, gives the following shades for the 1/2c with watermark: seal brown, light brown, dark brown, red brown. Good luck to those who can make out the right 'brown' from this description, but for normal persons this is impossible to reproduce. In a study of the Hong Kong series of the King Edward VII and the King George V, Nick Halewood and David Antscherl propose to describe the colours on the basis of the Pantone® system, a colour model accepted in the printing world. Its advantage is that it is a constant system, accessible for all, its disadvantage being that it does not contain very many colours. The Pantone® set for process colours contains a little over 3000 shades. By comparison, the Stanley Gibbons Stamp Colour Key contains 200, the Lipsia Philatelistische Farbentafeln 160.

Position of the paper

Normal |

Reversed |

Inverted |

Inverted-reversed |

The paper can be fed into the printing press in different ways: with or against the grain.

The stamps on watermarked paper were all fed into the machine in the same way, the low values with the watermark in an upright position, the dollar values with the watermark lying on its side. There are at least four ways in which the watermark occurs in the stamps (see drawing, seen from the reverse of the stamp). Although there is no prescribed way of delineating the watermark, it is inverted-reversed in by far most of the Waterlow stamps. The other positions occur, but they are rare, 2 to 3% at the most. Aglen reports 12 stamps with watermarks in a different position, I have found 14 myself, together this makes: 17 reversed, 6 inverted and only 3 with a 'normal' watermark.

The position of the paper used for the stamps without watermark, with or against the grain, results in differences in size between the stamps. The differences can amount to approximately 1/2mm in length. Strangely enough, this phenomenon only occurs from about 1909 onwards. It is not known whether this indicates the introduction of a different type of paper, with other shrinking properties, or whether the paper was cut in a different way.

Perforation

The Waterlow issues are characterized by a large number of perforations. Seven of these are represented in the file-copies. They are all line perforations. Until now, only the Stanley Gibbons Instanta Perforation Gauge has proved useful for measuring the subtle differences in perforation. With this gauge, it is possible to work accurately in tenths, which is not possible with the 'normal' perforation gauges. The following perforations are known:

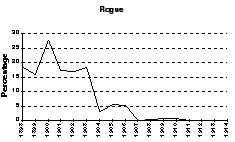

Rogue:

A very irregular perforation comb, with a perforation between 12 and 14. Its construction is as follows: one piece 13.5, followed by 7 holes 14, 11 holes 13.5, 126 holes 13.9, 7 holes 12, 18 holes 12 3/4 and the remainder 14. Stamps perforated with this comb therefore show all kinds of seemingly mixed perforations between 12 and 14. The comb was also used on the Red Revenues. The comb was used until about 1903.

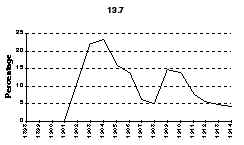

13.7

A regular comb, with perforation 13.7. The comb occurs in three stages. These originate as a result of the occasional breaking off of a tooth, so that the comb had to be re-bored. The comb was first used in February 1902, probably as a replacement of the 13.85 comb. This comb was also used on the London print of the Junk-series.

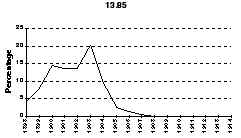

13.85

A regular comb, with perforation 13.85. Used from the beginning until the last in the January 1902 file-copies. Whether this really was the last use of this comb remains unclear.

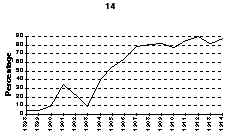

14

By far the most frequently occurring comb. It is a regular 14. There must have been several combs with this perforation. The first group contains the combs with thin teeth, until about 1904, after that combs with thicker teeth. There are minor differences. It is not always possible to distinguish stamps perforated with this comb from those perforated with section 14 of the Rogue.

14.4-14.8

An irregular comb, repeatedly with a 14.4 part of about 60 mm, followed by a 14.8 part of again 60 mm.

15

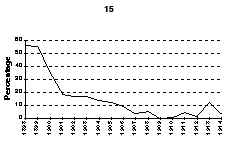

A reasonably regular comb, with a perforation between 14.8 and 15.0. Also used on the Red Revenues and still in use for the London Junks. At times it is difficult to ascertain whether a stamp belongs to this perforation or to the 14.4-14.8 group.

16

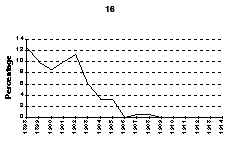

A more or less irregular comb, with values between 15.5 and 15.9. Most stamps are between 15.8 and 15.9. Used from the beginning until 1902.

13.5 (?)

The file-copies only indicate the above perforations. In their collections, Beales and Aglen also found some stamps with a 13.5 perforation. If these measurings are correct, and there does exist a comb with perforation 13.5, this perforation must be very rare. Among the approximately 5000 stamps I have measured there is not a single one with this perforation. There are a few later stamps with 13.6, but as far as I am concerned these come under the 13.7 comb.

Mixed perforations

As a result of the way in which Waterlow's executed the perforations there are quite a few stamps with perforations missing on one side. Sometimes these mistakes were discovered in time and repaired with a different perforating comb. This results in mixed perforations. These are very rare, much rarer than the partly imperforate stamps.

A survey of the perforations

Table 4: A survey of occurring perforations

Value |

Rogue |

13.7 |

13.85 |

14 |

14.4/8 |

15 |

16 |

1/2c wmk |

X |

* |

A |

X |

X |

X |

X |

1/2c |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

1c wmk |

X |

* |

A |

A |

X |

X |

X |

1c |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

2c wmk |

X |

* |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

2c deep red |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

2c deep green |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

3c |

|

X |

X** |

X |

X |

X |

|

4c wmk |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

4c deep chestnut |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

4c scarlet |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

5c wmk |

X |

* |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

5c salmon |

X |

X |

A |

X |

X |

X |

X |

5c orange |

X |

X |

A |

|

X |

X |

|

5c rose |

X |

X |

A |

X |

X |

|

|

5c mauve |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

7c |

|

X |

X** |

X |

X |

X |

|

10c wmk |

X |

* |

A |

X |

A |

X |

X |

10c deep green |

X |

X |

A |

X |

X |

X |

X |

10c blue |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

16c |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

20c wmk |

X |

|

X |

A |

X |

X |

|

20c |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

30c wmk |

A |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

30c |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

X |

|

50c wmk |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

50c |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

$1 wmk |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

$1 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

$2 wmk |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

$2 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

$5 wmk |

X |

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

$5 |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

* Aglen reports this perforation for the stamps on watermarked paper, this is highly unlikely because the perforation 13.7 was not introduced until February 1902. This is long after the last stamps on watermarked paper were printed.

** Aglen also mentions these perforations, again unlikely because perforation 13.85 had already been discarded by the time these stamps were issued.

The places marked with an A are additions to the Aglen/Beales list.

Random check, based on 5211 stamps for the survey and approximately 2200 stamps used for the distribution of the perforations per year.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Time-trend for the whole period

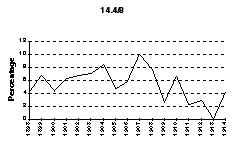

When we consider the whole period 1898-1914, perforation 14 appears to be the most frequent by far. It occurs in about 60% of the cases. Only perforation 15 barely exceeds 10%. When we consider the distribution per year, based on the cancellations on the stamps, we get a more variegated picture. In the period until about 1900 it is mainly perforations 15, Rogue and 16 that dominate. The perforations Rogue, 13.85 and 16 are discarded somewhere during the period 1902-1903, while a new perforation, viz. 13.7, is introduced in 1902. From 1907 onwards, about 80% or more is perforated 14, although 13.7, 14.4-14.8 and 15 are used until the end. This may be confirmed by the London Print of the Junk-stamps (also printed by Waterlow & Sons), where we also find these four perforations (13.7, 14, 14.4-14.8 and 15) The curious perforation 14.4-14.8 is used throughout the period, albeit only for small numbers, about 10% of the stamps at the most. A survey is presented in the diagrams at the end of this article. The first diagram shows the percentage of occurrences for each perforation in the measuring of 5211 stamps (all the values and periods together). The other diagrams show how the use of the different perforations proceeded over the years.

The approximately 2200 stamps with the year legible in the cancellation stamp were used for this. Statistically speaking, these are rather low numbers, so that no far-reaching conclusions may be attached.

Perforation errors

As a result of Waterlow's specific method of perforating, which involved regular turning over of the sheet, many perforation lines were forgotten. This yields the large quantities of 'imperforated between', 'fantails' etc. A complete list of these deviations is in preparation.

Counterfeits

Very few counterfeits of the original stamps are known to exist. There are counterfeits of the 'Japanese tourist sheets', of which I have so far only seen the 30c. Of the postal counterfeits, only one is known, viz. the 4c red with a Statistical Department overprint. It is a lithographic counterfeit on white paper. A few hundred copies are known, all with parcel post cancellation stamps. A counterfeit of the 2c green (litho), with status unknown, has recently been found in Kathmandu, printed on sheets of twice 12 stamps (Shrestha, 1995). There are large numbers of counterfeits of the imprints and the overprints, especially the Provisional Neutrality imprints have been forged in large quantities.

Any comments are very welcome and will be forwarded to the writer. Please send your comments to info@dandotra.com

(to be continued; a second article on the Waterlow Issue will be published in 'China Filatelie' later this year; look for the English translation on the D&O Website!)

Bibliography

Through the years, there have been quite a few publications on the Waterlow stamps. The most important of these are 'The Waterlow Issue of 1898' and 'Notes on the Waterlow Dragon Issue'. Some of the sources quoted in this article are the following:

Beales, K.H. and E.F. Aglen

The Waterlow Issue of 1898

London, The China Philatelic Society of London, June 1987

De Villard, R.A.

Proposed Stamps etc. & Postcards for the Imperial Chinese Post memos

Beijing, 1991

Hill, Lee H. ed.

Ma's Illustrated Catalogue of the Stamps of China. Volume I- Empire.

Tampa, Hill-Donnelly Corporation, 1995

Holcombe, Peter

1898 Dollar Value $5 with Watermark in Journal of Chinese Philately No. 271 (Vol.38 No.2)

London, The China Philatelic Society of London, December 1990

Lowe, Robson

China. The History of the Waterlow Dies. Appendix of the Journal of Chinese Philately No. 241 (Vol.33, No.2)

London, The China Philatelic Society of London, December 1985

Morgan, Henry G.

Notes on the Waterlow Dragon Issue in The China Clipper Vol. 16, No. 3

The China Stamp Society, Inc., April 1952

Report on the working of the Post Office for the year 1905.

Shanghai, Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs, 1906

Shrestha, Ramesh

The Mysterious 2 Cents Chinese Imperial Post Stamp in Journal of Chinese Philately No. 299 (Vol. 42, No. 6)

London, The China Philatelic Society of London, August 1995

So, Benny

A rare and unique discovery of the original drawings of the 'Imperial Chinese Post' drawn by R.A. de Villard in The China Clipper Vol. 35, No. 6

The China Stamp Society, Inc., September 1971

Corrections

In the first part of this article I stated that there are 4 perforations of the London print of the 'Junks' stamps extant. This appears to be incorrect. As Ed Boers has shown, in a 1986 issue of the Bulletin, only perforations 13.7, 14 and 15 were used for the London print.

Numbers printed

In the first article, it was assumed that the numbers of stamps printed, as published in 'The Waterlow Issue of 1898', are based on the archives up to April 1912. Meanwhile, the library has acquired Chow's original publication (1937). This book mentions the numbers of stamps issued until 1 January 1913. For the watermarked stamps, the numbers mentioned in 'The Waterlow Issue of 1898' were used. A small part of the «c with watermark was used for the B.R.A. overprints, the number of which is not known. The survey below is based on this in formation:

Plates

In the meantime, plate number 6 of the 3 cents stamp has been located.